The proliferation of the wellness agenda (and industry) over the last 10 years has closely matched the spread of mental illness in the western world. This is only a rough association, though it would seem that as individuals and as a society we have been driven toward a search for answers for this very modern ailment which is affecting more and more of us.

Well-being drives mental health – enables it; and vice versa. Mental health is confidence, self-esteem, self-efficacy, satisfaction, and contentment. While it is normal for the mood to fluctuate through highs and lows from day-to-day, this general sense of ease should be the default state – where we spend the majority of our time. It accompanies a level of cognitive and emotional functioning that enables us to fully enjoy and appreciate the events and people in our life. Mental illness, on the other hand, cripples the well being of the person. Feelings of overwhelm, obsessiveness, dissociation, and exceedingly high or low states (to name just a few) are completely normal, but it is when these feelings become persistent, become part of our default state, that mental illness starts to set in.

The ‘mental health problem’ is now well recognised – we know the stats are bad though they still manage to raise an eyebrow. For instance, the World Health Organisation has long been forecasting an explosion of mental illness, with estimates such as:

- by the year 2020, depression will be the second leading cause of disability throughout the world, trailing only ischemic heart disease (World Health Organisation, 1996); and

- by 2030, mental illness will be the number 1 cause of lost work time (World Health Organisation, 2008).

Despite the doom and gloom, the evidence is strongly in favour of the view that the mental health of the population can be improved upon simply by returning to a few basic tenants of good health, things we’ve always known to be true and which are almost entirely within our control. Though, while lifestyle and the pursuit of wellness is an effective treatment and preventer of mental illness the advancement of these remedies is hampered by an ongoing stigma associated with mental illness, imposed by both the individual upon themselves, and by the people surrounding affected individuals. This stigma disempowers us to take our own remedial action. Once we remove the stigma we can, as individuals in everyday life (as opposed to governments and foundations), stop tip-toeing around the issue because we think it’s too uncomfortable, scary or complicated.

To get to the essence of the ‘mental health problem’ we propose that we need to reconsider the very meaning of mental illness so that we do not become clouded from the core truth of the matter: in many cases we have the power to help ourselves by following a simple set of lifestyle behaviours which have a profound effect on mental health improvement, and mental ill-health avoidance.

Are we really so sick?

It seems a basic point but too often it is overlooked: in order to have an informed discussion about mental health then it helps to understand just what it is. To get into the right mindset for the distinction we are trying to make consider the debate that has been brewing for many years now regarding the diagnosis of ADD or ADHD (attention deficit hyperactive disorder) in children. Because of the sensitivity of the implications of this diagnosis – the medication and ’special’ treatment of our kids – this debate has been rigorous and has gone on to explore the problems generally with psychiatry as a science. For example, is this a problem with the child or are there environmental causes which can explain the behaviour? Perhaps it is even unwarranted to call this behaviour problematic. To wit, have our standards shifted such as to become intolerant of a child’s normal tendency to push boundaries? Or, have our modern parenting standards deteriorated to the point of failing to imbue a modicum of discipline in children?

We make this point at the risk of running off along a tangent because it is familiar and emotive for many, and illustrative of the challenge we face with regards to the seemingly inexorable spread of mental illness amongst us. The simple but very blunt question is: are we as sick as we think we are?

In 2013 a report published in the Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry measured a 58% increase in the dispensing of psychotropic drugs (drugs for mental illnesses) over the period from 2000 to 2011, including a 95% increase in antidepressants (Stephenson, Karanges, & McGregor, 2013). Could the mental health problem legitimately have gotten so big so quickly? Consider that psychiatry, as opposed to other disciplines of medicine, offers no pathology (biological tests) to support its diagnoses. For example, consider this statement by Allen Frances, Psychiatrist and former Task Force Chairman for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition):

“‘Mental illness’ is terribly misleading because the ‘mental disorders’ we diagnose are no more than descriptions of what clinicians observe people do or say, not at all well-established diseases.”

What psychiatry does offer is effectively a checklist of symptoms to be subjectively interpreted by the psychiatrist. That checklist is put together in texts like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is used worldwide by clinicians, researchers, regulation agencies, and even the legal system. It is considered one of the most important reference texts for any practicing psychiatrist yet even a book of this importance and influence is collated by a committee based on the collective experience of psychiatrists. It is, in essence, a subjective text, and not without criticism from various commentators because of this.

For instance, noting that each edition of the DSM continues to expand the number of identified diagnoses, some critics have argued that the financial relationships that many of the contributing authors of the DSM have with the pharmaceutical industry demonstrates a conflict of interest and suggests a motive to drive up the incidence of mental disorder diagnoses (Cosgrove, Krimsky, Vijayaraghavan, & Schneider, 2006). But quite apart from the alleged ulterior motives of influential psychiatrists is the pragmatic and eloquent criticism from the British Psychological Society that “clients and the general public are negatively affected by the continued and continuous medicalisation of their natural and normal responses to their experiences… which demand helping responses, but which do not reflect illnesses so much as normal individual variation” (British Psychological Society, 2011).

Demystifying Mental Illness

Herein lies the crux of our point. One of the great challenges with our ‘mental health crisis’ is realising that the goal posts (defining criteria for mental illness) have widened significantly in only a matter of decades. This is problematic for a number of reasons. First and foremost because we apply the same stigma, very often self-imposed, to a mental health diagnosis as generations upon generations have in the past. Once upon a time – not that long ago – being mentally ill meant losing one’s mind. This was poorly understood and viscerally feared by the masses. Nonetheless, mental illness was narrowly defined. Nowadays, rightly or wrongly, mental illness as a diagnosis has grown and can potentially include such natural and transitory states as severe grief, melancholy, and natural responses to stress. For sure, people need help when they are facing these challenges, but the label of mental illness is damaging because our slow to move perceptions of mental illness bring about shame in the victim and drive them underground, and this is when more serious issues can fester.

The second challenge with the widened goalposts is that people are driven into medical treatment sooner and sooner by the application of labels such as depression or anxiety. Medical treatment is certainly warranted in serious cases and it is also imperative that a suffering person seeks help regardless of the severity of their condition, but the early medicalisation of those cases which fall into the “widened goal posts” categories only serves to deepen the stigma: “I am taking medication so there must be something wrong with me.” Self-help and support groups are far better in these situations, particularly if the labels can be removed. Seeking help because you’re feeling down or overwhelmed is easier to broach with people than the definitive statement “I have depression/anxiety disorder.” Applying labels in this way through earlier medicalisation ultimately disempowers the victim. They relinquish a degree of self-determination about their affliction because they no longer feel qualified to address it themselves.

Get Well Soon

Consider the case of an injury, say a sprained ankle. We understand this well. There is soft tissue in the ankle and if over stressed it’ll swell up and be sore for a short period of time, but it’ll get better. In most cases you simply apply RICER: primary treatment being Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation. If severe, then we Refer (to a doctor). Being well understood and absolutely incidental to everyday life there is no stigma, quite the opposite in fact. People can see and understand your injury and are able to act sympathetically or empathically towards you: “Take a seat, have a rest”, “Can I help you down those stairs.” You do what you need to do and you get the help you need from people around you, and in a short period of time, you’re better. The common cold is another one of these well-understood afflictions which we all succumb to at some point. No stigma, and when not severe, no need for doctors.

There is another dimension to this analogy. How many people get through life without ever getting sick or injured at some point? How many athletes are in top form all of the time? We don’t consider injuries, mild infections or an athlete’s dip in performance unusual because it is unrealistic to expect otherwise. Somehow the same does not apply to mental health – we are deluded into thinking that we ought to be operating at maximum cognitive and emotional capacity all of the time. When we afford each other little tolerance for deviations from some rough, socially construed sense of normality, or when we punish each other for supposedly projecting weakness, we deepen the mental illness stigma. Constant peak performance is a fiction which we must accept, even if we are striving for it. Mental illness, particularly the variety of ‘low severity’ conditions such as depression and anxiety, are injuries. Injuries need attention, time to rest, help from the people around us, but allowing ourselves to make deeper inferences about a person’s character must be avoided.

From Mental Illness To Mental Wellness

“When clients present for therapy, they are often already under stress. Symptom reduction is an important facet of therapeutic care, however, due care and attention to alleviating systemic physiological stress associated with the quality of basic lifestyle can strengthen the foundations of resilience and pave the way to stronger mental health.” (Skeffington, 2013)

Most people understand and accept evolution, neatly summed up in the maxim “survival of the fittest.” What is lost in this next statement is the mechanics of evolution – the need for some kind of external stressor in the species’ environment to challenge their ability to exist. What is also lost is the perception that evolution only applies to species and takes place over long periods of time. In truth, evolution is reflected within every organism down to a cellular level, and at this level occurs rapidly. When we talk about evolution at a cellular level within an organism the word we are probably more familiar with is conditioning, or simply, training.

Training induces a measure of stress. Our bodies respond, rebuilding cells in the image of the stronger cells that survived the stress so that as a whole, the organism is not only prepared for the next stressor but better equipped to deal with it than before. Each bout of stress endured by the body, so long as it doesn’t breach a certain upper threshold, induces a response which lifts that upper threshold of tolerance. This is called super compensation, and it is very well understood and exploited by coaches of elite athletes who systematically and incrementally build an athlete’s physical capabilities by inducing increasingly larger doses of stress throughout the training regime.

The example of the elite athlete is a convenient illustration because instinctively we all understand this process, but, three very important and more general points need to be taken from this example:

- The evolutionary/super-compensation effect does not only apply to physical capabilities. It applies to our response to any form of stress, even mental stress. It also applies to skills: practice makes perfect.

- Our mental and physical faculties are interrelated. What we do physically can help us psychologically. This has been proven empirically time and again.

- Without training (i.e. the purposeful induction of manageable bouts of stress) we either stagnate or enter into involution. Involution is where the body perceives that it need not maintain a higher level of adaptation and declines to a more ‘regular’, that is to say, weaker, state. Any athlete gets weaker when they stop training. Use it or lose it.

This evolutionary response and the avoidance of involution is the very essence of the “foundations of resilience” referred to by Dr. Petra Skeffington in the extract above. This is where wellness becomes an essential aspect of the response to the mental illness problem. Wellness is the truest sense of preventative medicine: making yourself stronger and in doing so, less likely to fall victim to persistent unhealthy mental and emotional states. However, a conceptual shift needs to be made, where we stop visualising wellness as some kind of stable plane we travel along because we undertake calming activities and seek ways to soften the blows of life. In truth, wellness is the product, not the process. The process is actually volatile with ups and downs representing the training stimuli we inject into our lifestyle and the periods of recovery after these stimuli. The result, the appearance of stability, is actually the median state running through these ups and downs.

Seeking wellness is actually about training the body and mind to be stronger so that we are galvanised from the gradual deleterious effects of the low-level, chronic style of stress which seems to be a side effect of modernity. With this training, we essentially lift our stress tolerance threshold above the level that we generally sustain on a day-to-day basis. Have you ever wondered how certain people seem to be able to happily manage through life’s challenges – always keeping their cool despite the situation? These people are not superhuman; they may just be better trained. *

* We should note that predisposition to stress and extreme moods is real and no doubt a greater challenge for those affected. All the more reason to train yourself to be able to prevent the onset of more serious or long-term issues.

Training For Wellness – A Holistic Focus

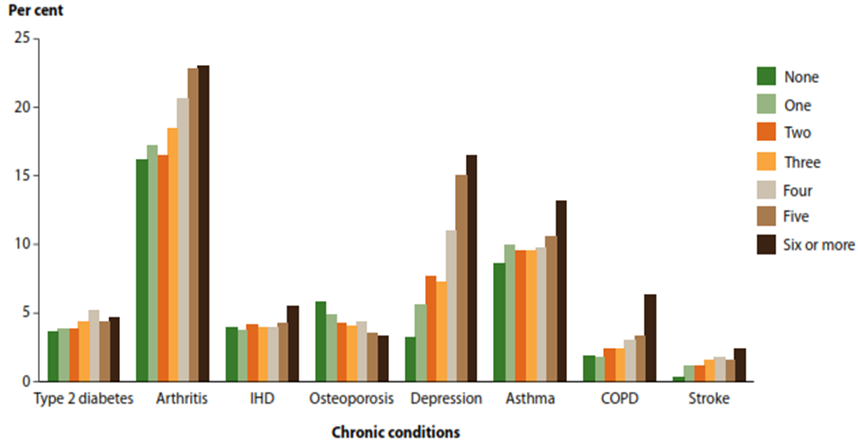

In a 2012 report compiled by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, a range of health risk factors were measured against the incidence of specified chronic conditions which are currently plaguing Australians at all ages. The risk factors tested included: high-risk smoking and alcohol behaviours, physical inactivity, insufficient fruit and vegetable intake, weight (measured via BMI as well as waist circumference), and blood pressure.

Figure 1 shows the results of the number of risk factors exhibited by people with chronic conditions. While this doesn’t necessarily show causality, that is, demonstrating unequivocally that the presence of one risk factor or another causes the given chronic condition, the correlation is clearly evident – the more lifestyle risk factors you exhibit, the more likely you are to fall victim to a chronic condition. Across the chronic conditions tested, this relationship between risk factors and incidence is most dramatic in relation to depression, a common mental illness. This demonstrates that in order to steer clear of depression we need to be careful to manage our lifestyles properly on a number of fronts because just one additional risk factor significantly increases your chances of falling victim. Training for wellness is multifaceted and cuts across all of these risk factors.

Figure 1: Numbers of risk factors by selected chronic condition.

The risk factors tested included: high-risk smoking and alcohol behaviours, physical inactivity, insufficient fruit and vegetable intake, weight (measured via BMI as well as waist circumference), and blood pressure. Source: (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012)

Physical Activity

The physiological link between exercise and mental health is only loosely understood at this time. The challenge is that, as pointed out earlier, psychiatry as a science offers no definitive pathology, only behavioural hallmarks considered indicative of a disorder. Nonetheless, there most certainly is an observable positive relationship between exercise and mental health. Various studies have used exercise to treat the ‘mild’ forms of mental illness we referred to earlier – anxiety and depression. One such study found exercise was as effective as anti-depressant medication in the treatment of mild depression (Mead, Morley, Campbell, McMurdo, & Lawlor, 2008). Another review summated the results of 27 studies into the effect of exercise on anxiety and found a statistically insignificant difference between medication and exercise as a treatment for this disorder (so why medicate when exercise is as effective?). Notably, exercise was found to be more effective than traditional relaxation style treatments, such as yoga, group therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and meditation (Wipfli, Rethorst, & Landers, 2008).

There are likely many contributing factors behind this link. Among the hypotheses is that exercise improves hormone regulation which influences brain chemistry. It is suggested that exercise helps us flush the system of the stress hormone cortisol. Exercise is itself a form of stress on the body and it is likely that the repeated exposure to small bouts of stress in this fashion results in smaller secretions of cortisol in other stressful situations – that is, we learn to better deal with stress at a physiological level. The disturbance to homeostasis which exercise produces accentuates our normal, hormone-driven, daily peaks and troughs, which means that exercise can help us sleep better. Better sleep improves our mood and coping skills and enhances our resilience against anxiety and depression. Exercise also helps regulate our insulin responses to food, which means we regulate blood sugar levels better. Since the brain utilises only glucose (sugar) for fuel, delivering glucose in smooth and gradual doses rather than in volatile spikes and troughs may ultimately keep brain chemistry working optimally.

Tips to improve exercise and movement:

• Change your perspective, view exercise as an opportunity, not a chore. Keep repeating the mantra to yourself even if at first you aren’t convinced. This “fake it till you make it” internal dialogue will slowly alter your attitudes until exercise becomes something you want to do.

• Take every opportunity to move more in everyday life. Break up long periods of sedentary activity.

• Eat well and rest properly so that you do not feel tired when it is time to exercise. A poor diet with volatile spikes in blood sugar will often leave you feeling tired as your blood sugar ‘crashes’ after an influx.

• Try to remember that exercise invigorates, and you rarely feel mentally tired after exercise.

Balanced Diet

Like physical activity, the exact physiological mechanism which triggers better mental health outcomes when good diets are observed (or poor outcomes when poor diets are followed), still requires development. Nonetheless, the statistical link has been established in a number of studies. Importantly, this link is observed across countries, cultures and age groups, especially with regards to depression.

It has been suggested that levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that helps regulate sleep, appetite, and mood, are heavily affected by the type of foods we eat. Proper nutrition also influences the rate at which we recover from any stress, be it physical or mental. Without a good diet we can become worn down by the rigors of life, and this affects us mentally. The recurring theme here is that energy and mood go hand in hand. When we are tired we are very often irritable. When we are drained it is much easier to become anxious about a bad situation. Good nutrition helps tip the scales toward energy, ease, and fulfillment, and this bodes well for our mental health.

At an elemental level, food is survival. So, when we are satisfied nutritionally it makes sense that our hormones will allow us to be and feel at ease.

It has been suggested that serotonin, a neurotransmitter that helps regulate sleep and appetite and mediate moods, is secreted in response to the type of food moving through the gut. The vast majority of serotonin is produced in our gastrointestinal tracts and scientists think that this is why food can influence mood. At an elemental level, food is survival. So, when we are satisfied nutritionally it makes sense that our hormones will allow us to be and feel at ease.

Proper nutrition also influences the rate at which we recover from any stress, be it physical or mental. Without a good diet we can become worn down by the rigors of life, and this affects us mentally. The recurring theme here is that energy and mood go hand in hand. When we are tired we are very often irritable. When we are drained it is much easier to become anxious about a bad situation. Good nutrition helps tip the scales toward energy, ease, and fulfillment, and this bodes well for our mental health.

Tips to improve diet:

- Change your perception – diet is a lifelong habit, not a sudden and drastic short-term change which is ultimately unsustainable and unhealthy. Your diet is for your health, not for your body transformation.

- Start small. Remove ‘extras’ (sugar, butter, treats). Replace snacks with fresh cut fruit and vegetables and/or nuts.

- Prepare – food ready in advance will stop poor choices from happening before they even get in your head!

- Exercise and sleep well. Another as yet unexplained phenomenon, but observable nonetheless, is the tendency for people to eat better once they start exercising regularly. The two habits seem to be complimentary, so if you find it easier to get into exercise, start with this first and you may find that you naturally start to prefer a healthier diet. Getting the proper amount of quality sleep will also improve perceived energy levels and therefore steer you away from ‘quick energy’ and comfort foods.

Sleep And Stress

The link between sleep, stress and mental state is somewhat better understood. Stress and depression have been shown to disrupt sleep in at least 65% of cases amongst adults (and 90% of cases amongst children!), and conversely, sleep problems very often precede the onset of mental illness (Cho, et al., 2008).

Self-esteem, entailing perceived capability to meet demands and responsibilities, self-management, emotional management and the perception of stress appear to sit behind these connections. Poor sleep lowers our coping thresholds creating a vicious cycle affecting confidence in oneself and emotional wellbeing. The technical phrase is “reciprocal association”, a relationship documented empirically between insomnia and burnout (Armon, 2009).

Luckily reciprocal associations have an inverse: a virtuous cycle. Getting the right amount of quality sleep strengthens self-esteem and coping skills, making us more capable, which alleviates stress and helps us sleep better.

The focus of most sleep recommendations is quantity. This is certainly important but incomplete – quality and quantity need to be achieved in order to get the best possible sleep. Bang for your buck is at least as important as the amount of time we spend sleeping.

It has to do with various stages of sleep. The deepest stages of sleep (stages 3 and 4) only last a short period of time, but it is very important to our daily revitalisation. We lose some of the restorative effects of sleep if we never achieve these stages or are broken from them prematurely. People with sleeping disorders very often only sleep lightly, even if they sleep (or are in bed) for a long time. When we sleep we go through cycles of each phase of sleep, however, typically the earlier part of the night or resting period is heavily weighted towards the deeper stages of sleep while the later part (or morning, normally) is spent more and more in REM sleep – the type of sleep we often associate with dreaming. This simply means if we have poor QUALITY sleep we typically cut shy our deeper stages of sleep inhibiting revitalisation, and if we cut short on QUANTITY we minimise REM sleep which helps consolidate memories and emotional experiences, ultimately affecting mood and energy together.

Sleep hygiene refers to practices which give you the best chance of getting a good quantity of quality sleep by programming the brain and the body to switch into sleep mode at specific times.

Tips to improve sleep hygiene and sleep quality:

- Get regular: Practice going to bed and waking up at roughly the same time, even on weekends.

- Bed is for sleep: do not let the body associate the bed with anything else except sleep, and sex. This means no watching TV, eating or “just lying about” in bed.

- Avoid caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine in the 4-5 hours before bed.

- Set a bedtime ritual – a process you go through when preparing to get into bed.

- Exercise: this helps create a stronger sleep drive as the body relaxes into a deeper rest state to compensate for the excitement of exercise.

Social And Environmental Factors

We’re often taught to choose our friends wisely. As youngsters your parents probably warned you about falling in with a “bad crowd”. Likewise, by way of analogy, if you’re into your squash you’ll always be keen to play a higher graded player because this forces you to improve your own game. This is the concept behind the adage that we need to run with lions if we aspire to do great things.

The influence of our social circle upon us is just another one of those things that we tend to know instinctively. It is nonetheless interesting when science proves these instincts right. The pervasiveness of social influence with regards to health behaviours was measured in one long-term study tracking obesity incidence across groups of friends and family for 32 years. The study – the first to examine this phenomenon – found that if a person you consider a friend becomes obese, your own chances of becoming obese rises by 57%. Among mutual friends, the effect is even stronger, with chances increasing 171% (Christakis & Fowler, 2007). The authors suggest that this social network effect carries over to a range of other health behaviours. Luckily, there are similar effects with regards to positive health behaviours. The power of your example within your social network can positively affect your friends and family, which is where your “holistic training for wellness” can yield broader benefits beyond your own physical and mental health.

Another important social and environmental factor to consider is your support group, and how you offer support to your family, friends, and co-workers. So far, the tenants of health we have written about cover matters which are entirely within our control. We can’t always choose the people close to us (or at least, not easily), but we can control how we act toward them, and this example, as in the social network effect, can be a powerful contributor to the way your support circle affects you.

Acknowledging that we are all susceptible to injuries or ailments at some point, it is important that we take a look at how we personally, and as a society, address ‘low severity’ mental illness. For example, if we recognise that the earlier medicalisation of mental illness has created the illusion that we are not equipped to help a “mentally ill person” we can make that fundamental shift and realise that we are all equipped to help an injured person in the same way as we are equipped to help a person with a sprained ankle.

Personal Management And Effectiveness

Personal management refers to how we manage the events or circumstances in our life. We are familiar with concepts like reactivity versus pro-activeness, optimism versus pessimism, and organised versus unprepared. These are life skills and vital personal characteristics not just for career progression and performance, but for addressing the various challenges one has on their plate at any point in time with grace and aplomb. In many ways strong personal management skills allow us to rise above the irritating and menial aspects of life without being clouded, drained, or tied down by them. Personal management gets us out of the rut and allows us to experience the utterly empowering feeling of making progress in our life.

The two key elements of personal management are:

- Organisation and Time management – placing yourself in control of the pace of tasks which fall on your plate and properly managing the expectations of others in relation to deadlines.

- Mood / State management – knowing how to tap into the best emotional state to tackle a given task. Knowing when to push hard because you are in the right state for it, and when to pull back because you aren’t.

Tips to improve personal management

- Use a time management system (there are many!). It doesn’t matter which one, just as long as it’s effective and easy for you, personally, to stick to. Usually, the simplest systems work best.

- Be aware of your natural/first response to circumstances. Practice mindfulness, seeking to consider your responses more carefully before you act.

- Establish a support network or avenue to receive help when needed. Especially useful in the workplace when you can delegate or ask a colleague for assistance.

- Take time to work on the overall state of your body and mind, like exercise, or reading or just relaxing.

The Killers – drugs, smoking, and alcohol

Avoiding the killers, or at least minimising exposure for general health is obvious. The link with mental health is also well established. Studies abound of links between alcohol abuse, smoking, and drug use, particularly long-term, and diminished stress management capability, heightened anxiety, depression, and extreme moods, including paranoia, aggression, and hallucinations.

Most of this is quite well known, and if we were all purely rational beings, then it is likely that there would not be problems with the abuse of any of these substances. The truth is that these substances are frequently a crutch – a coping mechanism used to alleviate pressure in another area of a person’s life. We know the risks, but we are looking for a temporary release, an outlet. Getting clean of substance abuse will certainly help you decrease your risk of falling victim to mental illness but the potential for relapse remains if the underlying drivers are not addressed. To achieve a more permanent outcome, this is where the help of a specialist organisation can be very effective. Organisations like Quitline (for smoking) and Holyoake (drug and alcohol counseling) have proven to be very effective in addressing these underlying factors.

The Warrior Mindset

At Warrior Wellness we refer to the Warrior Mindset: a positive, striving, resilient and disciplined mentality, built on the strength derived from being in command of one’s health and physical and mental states, and the skills acquired from practicing healthful habits consistently. The concept is, simply put, that holistically healthy habits are challenging to maintain, but they confer benefits beyond fitness. What we get from the practice of wellness, the adherence to disciplines is an elevated level of functioning in all aspects of our life, which makes us stronger people overall. Mental health and physical health work hand in glove, and the more we practice the habits which are the tenants of physical wellness, the more we reinforce the foundations of mental health. Practicing these habits is very much within our control, which means our mental health is also largely within our control.

References

Armon, G. (2009). Do burnout and insomnia predict each other’s levels of change over time independently of the job demand-control–support (JDC–S) model? Stress and Health, 25, 333-342.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Risk factors contributing to chronic disease. Canberra: Australian Government.

British Psychological Society. (2011). Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 Development. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Cho, H. J., Lavretsky, H., Olmstead, R., Levin, M. J., Oxman, M. N., & Irwin, M. R. (2008, Dec). Sleep Disturbance and Depression Recurrence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(12), 1543-50.

Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Eng J Med, 357, 370-379.

Cosgrove, L., Krimsky, S., Vijayaraghavan, M., & Schneider, L. (2006). Financial ties between DSM-IV Panel Members and the Pharmaceutical Industry. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75, 154-160.

Herring, M. P., O’Connor, P. J., & Dishman, R. (2010). The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients: A systematic review. Archives of internal medicine, 170(4), 321-331.

Lai, J. S., Hiles, S., Bisquera, A., Hure, A. J., McEvoy, M., & Attia, J. (2016, June). A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103 (6).

Mead, G. E., Morley, W., Campbell, C. A., McMurdo, M., & Lawlor, D. (2008). Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4 (CD004366).

Skeffington, P. (2013, February). Quality of Lifestyle: Building the foundations for better mental health. InPsych, 35(1), 1.

Stephenson, C. P., Karanges, E., & McGregor, I. S. (2013). Trends in the utlisation of psychotropic medications in Australia from 2000 to 2011. Aust NZ J Psychiatry, Jan:47(1), 74-87.

Wipfli, B., Rethorst, C., & Landers, D. (2008). Anxiolytic effects of exercise: A meta-analysis of randomised trials and dose-response analysis”. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30, 392-410.

World Health Organisation. (1996). The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

World Health Organisation. (2008). Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organisation.